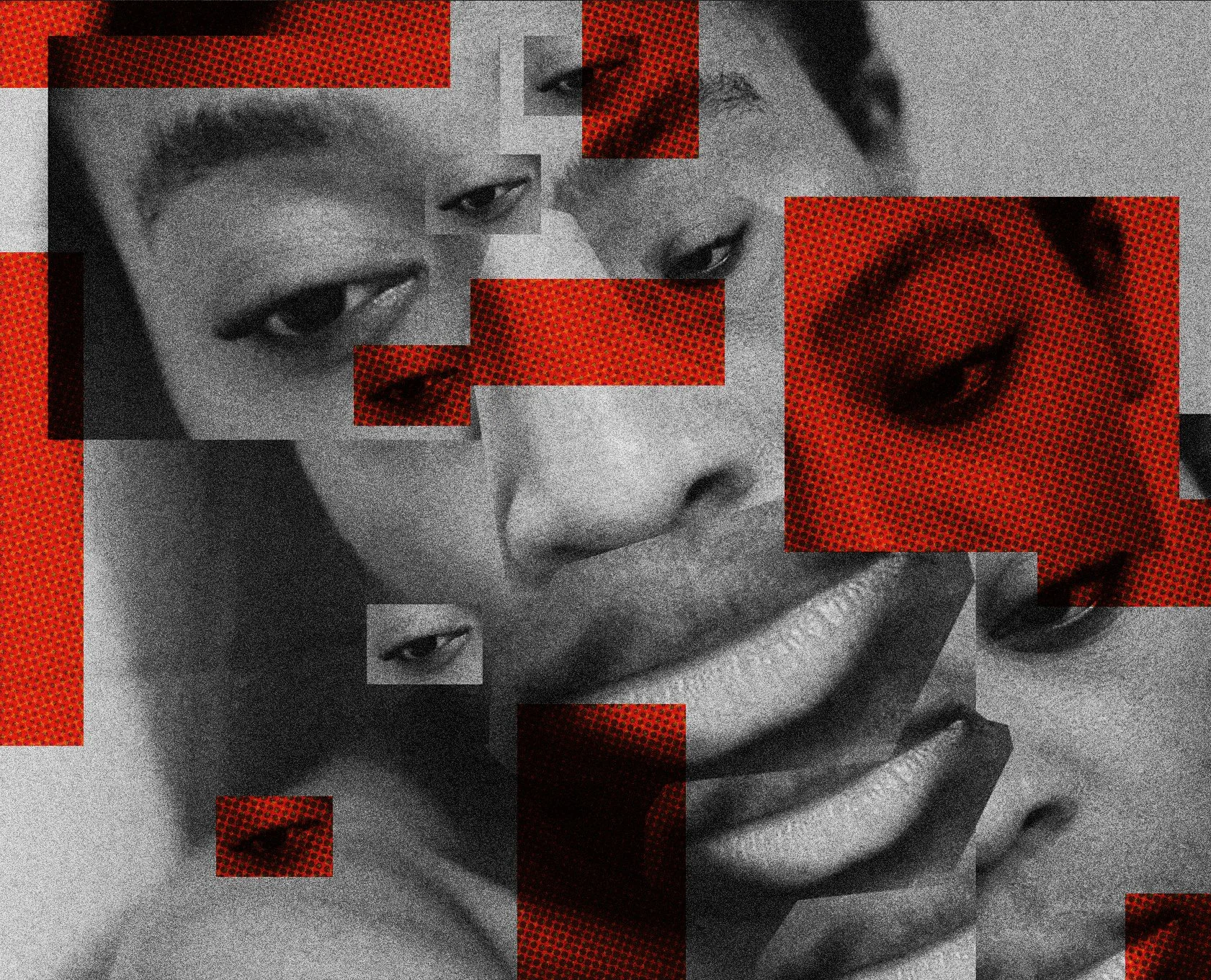

The Alien Within: Blackness, Weirdness, and the Right to Be Complex

“What do you do when you need something and the universe failed to create it? You create it yourself.”

Aaron Silverstein didn’t immediately understand this until he was deep in the edit, cutting together red-washed motel rooms and blue-bathed labs, that the words hit him. “I didn’t realize what it meant until after the film was done,” he told me. “When everyone tells you, no, you can’t have this. You’re going to have to build your own language. You’re going to have to build your own universe metaphorically, literally.”

The Infinite Husk, directed by Silverstein and starring Peace Ikediuba (Vel), and Circus-Szalewski (Mauro), is his own universe as a street-level, low-budget LA sci-fi about embodiment, the uncanny edges of Blackness, womanhood, and humanity. It's the kind of film that insists on its own complexity because its creator refuses to ask permission for his.

When I mentioned how rare it is to see Black characters allowed to be weird on camera, Silverstein immediately responded about how he was militant about the whole process of character creation and allowing that to flourish within the story. “There are white actors who get Oscars for playing weird characters, sad characters, crazy people, terrible people. Simply put, they get to portray the full spectrum of humanity. Traditionally, Black people get Oscars for saying yes sir, no sir.”

There are mornings when my body feels like an ill-fitting costume

For The Infinite Husk, he wanted more. Vel’s physical form is that of a Black woman who uses science and language to express a range of emotions that aren’t restricted to one form of execution. That execution was used to mold a story mission as representative liberation, and though built as sci-fi, the film’s emotional engine is existential.

For example, when Vel breaks down in the motel room, he wanted the film to inform that feeling of panic in the human body. When she solves the equation, it signals acceptance of shaping her own life on Earth.

In this essence of the body, the mind, and how that encompasses a whole human being, I kept circling back to my own body in relation to what I was watching unfold in the film. Not in a symbolic way, but in the very real sense of inheriting a form that has so often been the site of conflict. As a Black woman, I navigate many intersections including chronic health issues, hormonal shifts, anxiety, and a nervous system that betrays me on a daily basis. So witnessing Vel’s alien awkwardness read as familiar, opposed to otherworldly. There are mornings when my body feels like an ill-fitting costume, where even basic movements feel robotic. The film doesn’t have to shout about embodiment, it shows it. Vel’s asthma attack, her amusement at discovery, the sudden shock of feeling is where I recognized myself in the tension between presence and estrangement.

What lingered even more was the film’s insistence that complexity is necessary to the human experience. I’ve spent years operating in spaces (journalism, film, academia, even healthcare) where Black women are expected to flatten themselves for legitimacy by having to choose one aspect of our identity at a time that will be believable. You can be strong or sensitive, visionary or vulnerable, but not all at once.

The Infinite Husk rejects this forced binary. It gives the alien entity a Black woman’s body with the room to be strange, brilliant, disoriented, analytical, tender, and terrified in the same scene. Watching that felt like being granted permission to exist without shrinking and without apology.

The film also stirred something more spiritual. The Infinite Husk is a reminder of the quiet, often invisible push for survival. Living with disability, trauma, and ongoing health uncertainty means I’m constantly negotiating time the way Vel negotiates her own internal clock. Some days I’m ahead of myself, racing toward clarity. Other days, I’m trying to interpret signals I can’t figure out. But there’s a moment in the film where Vel solves an equation that struck me the hardest. Not because it’s triumphant, but because it frames understanding as an act of self-possession. I know this feeling all too well. It’s those rare moments when my mind and body briefly align, and remember that I still have control over my life.

In this way, Infinite Husk isn't about entertainment, at least for me. It mirrored the nonlinear journey of the human experience. Alienness is sometimes just the name we give to the parts of ourselves we haven’t learned to embrace with empathy. As someone who is constantly navigating systems that weren’t built for me to sustain, there was something revelatory in watching a character claim space in a world that she doesn't understand and vice versa. The film’s ethos in “build your own universe” resonates because…

for many Black women, especially those of us living at various intersections, creating our own universe isn’t a choice. It’s essential for survival.

Seeing that reflected onscreen felt like a reclamation of complexity I’ve earned the hard way.

During our interview, I expressed these thoughts to Silverstein in a roundabout way because those were the things I discovered about me while watching his film. However, I did ask him if there was anything he discovered about himself throughout The Infinite Husk creation, and he revealed he held a lot of pinned up anger. “I didn’t realize I was angry making this film.” I did a double take because that anger didn’t necessarily come across to me watching the film, but this goes back to the quote at the beginning of the article. He's angry that these kinds of stories are not told from a specified point of view. “If you’re waiting for the world to give you permission. It won’t ever get there,” he said. “We’ve got to make our world. We’ve got to make the one that we want to be in.”

Alienness is sometimes just the name we give to the parts of ourselves we haven’t learned to embrace with empathy.

I placed myself in his shoes and thought about what he really said. Of course Hollywood could be more diverse, and flexible with the type of stories told from cultural points of view. But, the fact that there are so many stories out there that we’ll never see the light of day because of the lack of resources would piss anyone off. Despite his anger, he’s proud of the ownership: “This film weirdly moves, walks, talks, sounds like the film that I intended to make. If someone hates it, I own that, but if they like it, then those are the people my film is for.”

I think by the end of the interview, Silverstein realized that he’d come face-to-face with someone who represents the exact demographic that his film is for. Bringing his work, empathy, work ethic and process full circle.