blasphemous structures: Alien communication in THe INFINITE HUSK

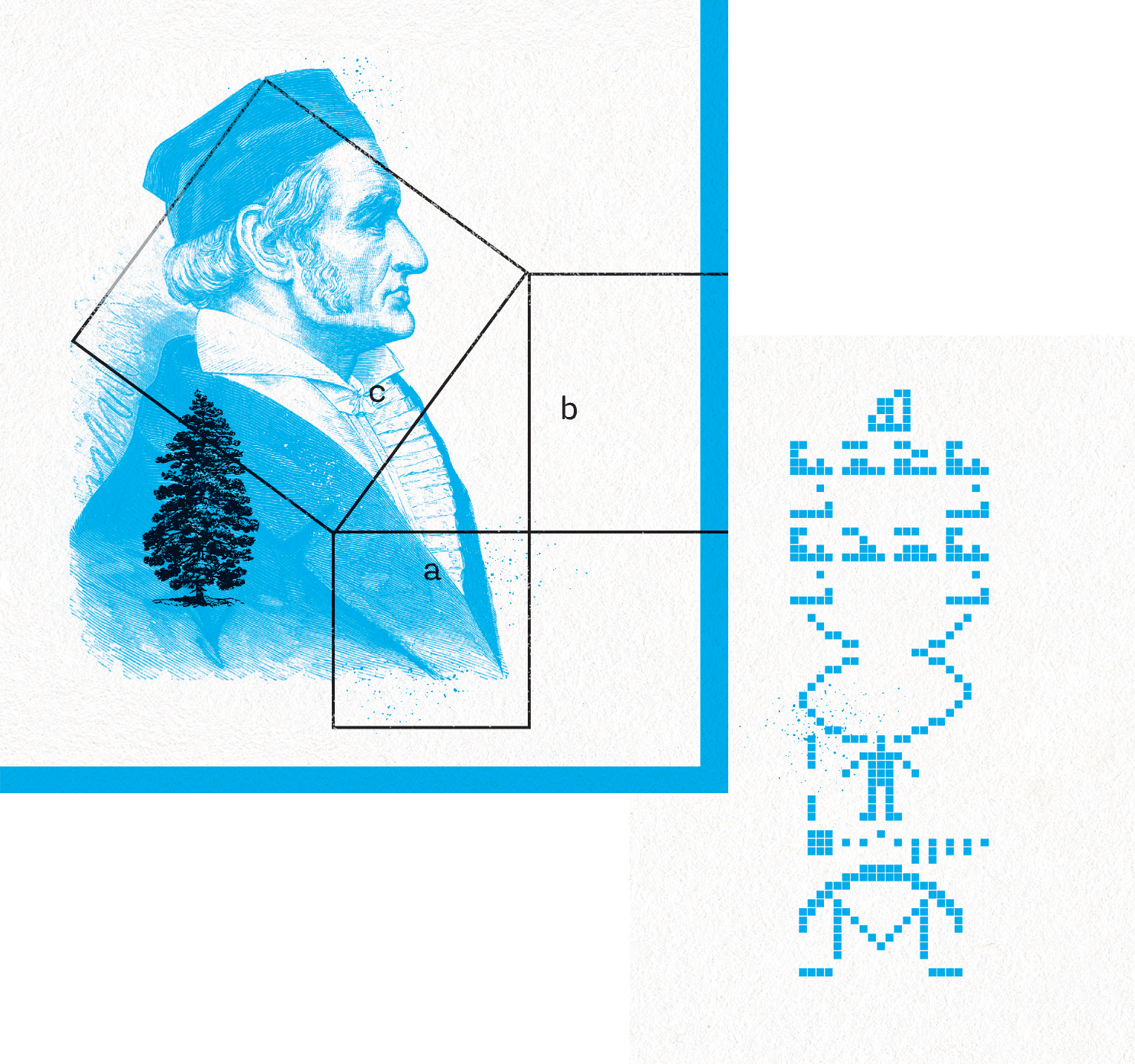

In 1820, the German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss proposed the construction of a gigantic proof of the Pythagorean theorem on the steppes of Siberia, planting pine trees and sowing wheat fields to form a visual representation of a fundamental principle in mathematics. The idea was that the shapes would be big enough to be seen from the moon, Gauss ultimately unrealized folly the first recorded human attempt to communicate with extraterrestrial beings.

Since then, humans have set the terms for these would-be encounters, using methods as diverse as radio waves, primitive bitmaps, crude drawings, microwave radiation, Morse code, and Carl Sagan’s famous gold record with (among other things) Chuck Berry singing “Johnny B. Goode” encoded onto it. One scientist at a joint Soviet-American conference in 1971 had perhaps the most novel idea: Take the world’s entire nuclear arsenal and blow it up on the far side of the moon, creating thermal radiation that would be visible from a couple of solar systems away.

All of these ideas and attempts have one thing in common: they’re examples of humanity projecting its ideas outward into the universe. The Infinite Husk flips this script, using human language and consciousness not as a method for humanity to explain itself to aliens, but for aliens to understand themselves. By fusing their consciousness with ours, the film’s “travelers” are able to use the fundamental building blocks of our systems of communication to create a “theory of everything” that goes far beyond simple human understandings of the universe.

The study of xenolinguistics, also known as astrolinguistics, has a philosophical bent, opening up fundamental questions about the nature of language itself. How can humanity assume, for example, that we are speaking to a species that perceives time the same way that we do? How do you convey something having happened or about to happen to a species that experiences past, present, and future as one continuous flow? Or, how do you explain pronouns to a species that does not consider individuals as discrete beings, but instead operates from a communal consciousness?

The Infinite Husk solves this issue — as well as the famous Fermi paradox — by putting its interstellar travelers into human “husks,” allowing them to see the world as we do. The thing that most intrigues the film’s alien visitors, the upside of being exiled onto our backwater planet full of suffering and death, is the concept of “seeing” something in your head, or what we humans call “imagination.” (Not all humans can do this either, to be clear — about 3% of the world’s population has something called aphantasia, which limits their ability to visualize images internally.)

Mauro, the older and more experienced of the “travelers,” is working on a theory of how, using the human brain as a conduit, “the description of a thing becomes the thing.” This is a fundamental question in semiotics, a broad and heady field of study that tries to understand how both linguistic — letters, words, sentences — and non-linguistic — colors, shapes, tones of voice — symbols come to be commonly understood across groups of individuals.

“If we read something, the human mIND has to create it,” Mauro explains to Vel, his younger and less experienced counterpart.

This process can get quite metaphysical, as Mauro references when he says that, due to minute changes in breathing and perspiration when a human imagines something, those thoughts, “quantum mechanically speaking, [are] becoming real and measurable.” His goal is to transcribe the aliens’ language into a form that’s legible to humans, a sort of extraterrestrial Prometheus who’s stealing the higher thought-forms of his species and transforming them into a written language.

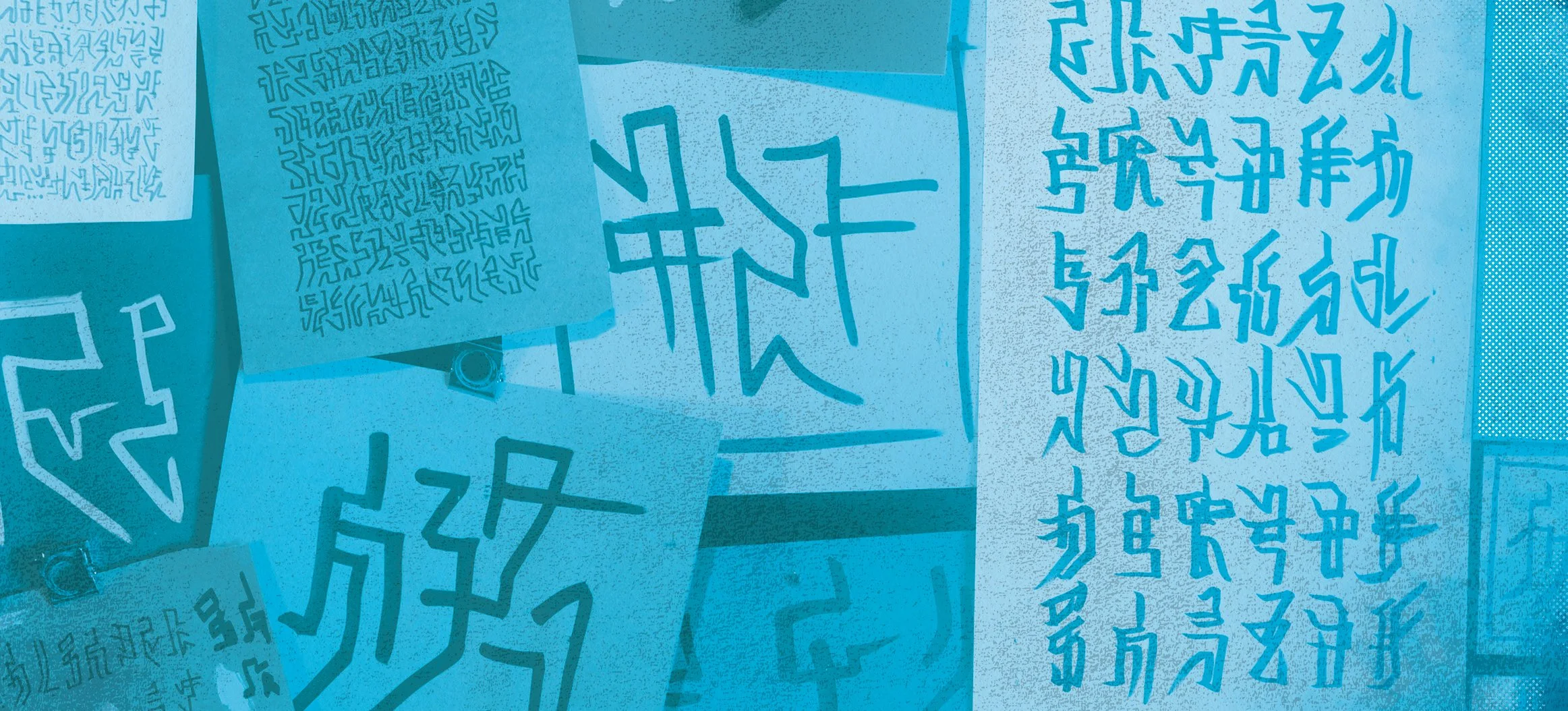

Mauro and Vel do this through a collection of ideograms, a written character that isn’t a simplified drawing of a concrete object— those would be pictograms, the earliest and simplest form of written language — but an abstract symbol that conveys the idea of something. Both pictograms (i.e., 山 shān; mountain) and more abstract ideograms (i.e.,下 xià; down) are important elements of Mandarin Chinese, Earth’s most commonly spoken native language.

Mauro and Vel’s system is similar, in that it adds brushstrokes to a symbol to increase the complexity of its meaning, and combines symbols to create new ones. Aesthetically, however, their language also recalls American street art, with elements of the Philly handstyle graffiti alphabet, the graphic pop art of Keith Haring, and the modified American Sign Language characters painter Martin Wong incorporates into his work.

The urban aesthetic of the film's alien language is no coincidence: Director Aaron Silverstein says that cinematographer and production designer Mitchel McKenzie initially sketched a completely different set of symbols that were impressive but a little too beautiful, “So then I drew a handful of symbols that were taller, skinnier, ‘meaner’, and far less polished that were designed to invoke tall buildings much like L.A.,” Silverstein says. “I wanted the symbols to invoke ‘blasphemous structures’ like the tower of Babel in the Bible. He saw those, immediately knew what I was after, and created entirely new symbols which became the language you see in the film today.”

The Infinite Husk’s “blasphemous structures” are part of another tradition: Conlangs, or constructed languages, attempts by humans to anticipate the communication needs of beings completely different from ourselves. Some of them are crafted without nuance, in order to avoid potentially dangerous cosmic misunderstandings. Others are more artistic in intent. One famous conlang is the Heptapod language, created for the 2016 film Arrival; that one is fairly abstract, but not as far out as Galactic Whalic, which revolves around gravitational vibrations created by the positions of black holes inside of an imaginary species of (you guessed it) galactic whales.

Many of these languages are also designed to be unintelligible and unpronounceable to humans in their spoken forms, leaving written transcription as the only mode of cross-species communication. On that note, it’s important to consider that we never hear Vel and Mauro speaking their native language, only reading it. Shots of Vel reading are juxtaposed with cosmic imagery, which — through the grammar of film editing — we are meant to pair together in a semiotics of meaning.

This makes the film rhyme, as the filmmakers use the visual language of film to tell a story about a race of extraterrestrials trying to create a language. Both groups are attempting to express emotions that can feel inexpressible: The awesome wonder of the universe, paired with the homesick ache Vel feels while beholding it. Vel’s hope of returning there, which later sours into cynicism and despair when she realizes just how much both Mauro and her handlers back home are keeping from her. The empathetic power of cinema sparks these emotions in viewers as well — emotions that will physically affect us, and therefore our environment as well. That makes The Infinite Husk, a film made up of digital files that must be translated through projectors and TV screens to be intelligible to the human brain, real, in the same way that imagining a bird makes it real.